A brief account of Tibet, its origin, how it grew into a great military power and carved for itself a huge empire in Central Asia, then how it renounced the use of arms to practise the teachings of the Buddha and the tragic conseguences that it suffers today as a result of the brutal onslaught of the Communist Chinese forces is given in the following passages.

Five hundred years before Buddha Sakyamuni came into this world i.e., circa 1063 B.C., a semi-legendary figure known as Lord Shenrab Miwo reformed the primitive animism of the Shen race and founded the Tibetan Bon religion. According to Bonpo sources there were eighteen Shangshung Kings who ruled Tibet before King Nyatri Tsenpo. Tiwor Sergyi Jhagruchen was the first Shangshung King.

Shangshung, before its decline, was the name of an empire which comprised the whole of Tibet. The empire known as Shangshung Go-Phug-Bar-sum consisted of Kham and Amdo forming the Go or Goor, U and Tsang forming the Bar or Middle, and Guge Stod-Ngari Korsum forming the Phug or Interior.

As the Shangshung empire declined, a kingdom known as Bod, the present name of Tibet, came into existence at Yarlung and Chongyas valleys at the time of King Nyatri Tsenpo, who started the heroic age of the Chogyals (Religious Kings). Bod grew until the whole of Tibet was reunited under King Songtsen Gampo, when tha last Shangshung King, Ligmigya, was killed.

The official Tibetan Royal Year of the modern Tibetan calendar is dated from the enthronement of King Nyatri Tsenpo in 127 B.C. This lineage of Tibetan monarchy continued for well over a thousand years till King Tri Wudum Tsen, more commonly known as Lang Darma, was assassinated in 842 A.D.

Most illustrious of the above kings were Songtsen Gampo, Trisong Detsen and Ralpachen. They are called the Three Great Kings.

The Great King Songtsen Gampo with his Nepalese and Chinese Queen

The Great King Songtsen Gampo with his Nepalese and Chinese Queen

During the reign of King Songtsen Gampo (629-49) Tibet became a great military power and her armies marched across Central Asia. He promoted Buddhism in Tibet and sent one of his ministers and other young Tibetans to India for study. He first took a Tibetan princess from the Shangshung King as his wife and then obtained a Nepalese consort. After invading the Chinese Empire he also obtained a Chinese princess as one of his wives. The two latter wives have been given prominence in the religious history of Tibet because of their services to Buddhism.

During the reign of King Trisong Detsen (755-97) the Tibetan Empire was at its peak and its armies invaded China and several Central Asian countries. In 763 the Tibetans seized the then Chinese capital at Ch’ang-an (present day Xian). As the Chinese Emperor had fled, the Tibetans appointed a new Emperor. This memorable victory has been preserved for posterity in the Zhol Doring (stone pillar) in Lhasa and reads, in part:

“King Trisong Detsen, being a profound man, the breadth of his counsel was extensive, and whatever he did for the kingdom was completely successful. He conguered and held under his sway many districts and fortresses of China. The Chinese Emperor, Hehu Ki Wang and his ministers were terrified. They offered a perpetual yearly tribute of 50,000 rolls of silk and China was obliged to pay this tribute

It was during his time that Samye, the first monastery in Tibet, was founded by Guru Padmasambhava, who also established the supremacy of Buddhism and coverted the indigenous deities into guardians of the Dharma. King Trisong Detsen also expelled the Chinese monk (Hoshang) and banished the Chinese Chan school of Buddhism from Tibet forever and adopted the Indian system. He also declared Buddhism as the state religion of Tibet.

During the reign of King Ralpachen (815-36) the Tibetan armies won many victories and in 821-2 a peace treaty was concluded with China. The inscription of the text of the treaty exists in three places: One outside the Chinese Emperor’s palace gate in Ch’ang-an, another before the main gate of Jokhang temple in Lhasa and the third on the Tibetan-China border at Mount Guru Meru. Eminent Tibetan scholars, Kawa Paltsek and Chogru Lui Gyaltsen, worked with Indian scholars, invited them to Tibet and prepared the first Sanskrit-Tibetan lexicon called the Mahavyutpatti.

In 838 King Ralpachen’s brother, Tri Wudum Tsen, ascended the throne. He tried to reinstate the Bon religion and persecuted the Buddhists. After his assassination by a Buddhist monk the kingdom was divided between his two sons. With warring princes, lords and generals contending for power the mighty Tibetan Empire disintegrated into many small princedoms and a dark period fell over Tibet during 842-1247.

In 1073 Konchog Gyalpo founded the Sakya monastery. His son and successor, Sakya Kunga Nyingpo, formulated the tantric traditions of the great scholars Marpa and Drogme and founded the Sakya sect. The Sakya lamas grew in power and from 1254 to 1350 Tibet was ruled by a succession of 20 Sakya lamas. The Mongols, who invaded many countries of Europe and Asia, also invaded Tibet and reached Phenpo, north of Lhasa. However, Prince Godan, the ruling Khan, was converted to Buddhism by Sakpa Kunga Gyaltsen, popularly known as Sakya Pandita, and the invading force was withdrawn. The next Khan, Kublai, was also converted to Buddhism by Sakya Pandita’s nephew and successor, Sakya Phagpa. In return, Kublai Khan gave recognition of full sovereignty over “the three provinces of Tibet : U-Tsang, Dhotoe and Dhome” to Sakya Phagpa.

The influence of the Sakya priest-rulers gradually declined after the death of Kublai Khan in 1295. In 1358 the province of U (Central Tibet) fell into the hands of the Governor of Nedong, Changchub Gyaltsen, a monk of the Phamo Drugpa branch of Kagyud school, and for the next 86 years, eleven Lamas of the Phamo Drugpa lineage ruled Tibet.

But, after the death of Drakpa Gyaltsen, the fifth Phamo Drugpa ruler, in 1434, power passed into the hands of the Rinpung family who were related to Drakpa Gyaltsen by marriage. From 1436 to 1566 the heads of the Rinpung family held power.

Meanwhile, Tsongkhapa Losang Dragpa, one of the greatest scholars of Tibet, was born in 1357. He founded Gaden, the first Gelugpa monastery, in 1409 and began the Gelug lineage.

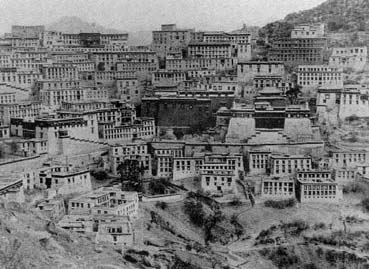

The Great Ganden Monastery

The Great Ganden Monastery

During the first decade of the 16th century, Tseten Dorje, a servant of the Rinpung family, with the help of some local tribes and Mongols, managed to gain control of Shigatse and the surrounding regions of Tsang province. From 1566 to 1642 Tseten Dorje and his two successors ruled Tibet with the title of Depa Tsangpa.

Sonam Gyatso, born in 1543, emerged as a scholar of great spiritual and temporal wisdom. He became the spiritual teacher of the Phamo Drugpa ruler, Drakpa Jungne. He was the Abbot of Drepung monastery and the most eminent lama of that time. He provided extensive relief to the Kyichu flood victims in 1562, founded Lithang Monastery in 1580 and Kumbum Monastery in 1582. He also successfully mediated between the various warring factions in Tibet. He converted Altan Khan to Buddhism and the latter conferred on him the title Dalai Lama meaning “Ocean of Wisdom” in 1578. As Sonam Gyatso was third in his line, he became the Third Dalai Lama, the title being posthumously conferred on his two previous incarnations.

A close spiritual relationship developed between Tibet and Mongolia. The Gelugpa sect grew stronger and gradually eclipsed the waning Sakya authority.

In 1642, the Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lozang Gyatso, assumed both spiritual and temporal authority over Tibet. He established the present system of the Tibetan Government, known as the Ganden Phodrang, “Victorious Everywhere”. After becoming the ruler of all Tibet, he set forth to China to demand Chinese recognition of his sovereignty. The Ming Emperor received the Dalai Lama as an independent sovereign and as an equal. It is recorded that he went out of his capital to meet the Dalai Lama and that he had an inclined pathway built over the city wall so that the Dalai Lama could enter Peking without going through a gate.

The Emperor not only accepted the Dalai Lama as an independent sovereign but also as a Divinity on Earth. In return the Dalai Lama used his influence to bring the warlike Mongols into acknowledging the Emperor’s sway in China. Henceforth, there started a Priest-Patron relationship which brought a new element into the relations of Tibet, China and Mongolia. Another important event was the statement of the Fifth Dalai Lama that the line of the first Panchen Lama, Choskyi Gyaltsen, who was one of his tutors, would continue.

The glorious reign of the Great Fifth was followed by a period of intrigue and instability. To start with, the powerful prime minister, Desi Sangye Gyatso, had kept the death of the Fifth Dalai Lama secret for fifteen years in order to complete the construction of the Potala Palace and also to ward off possible interference from the Manchus, who had become increasingly powerful in China. When the Sixth Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyatso, was finally enthroned in 1697 he turned out to be an embarrassment to the Desi and his associates, refusing to take interest in the affairs of state and leading a frivolous life. Circumstances arising from the behavior of the young Dalai Lama and also the personal conflict between the Desi and Lhazang Khan, the grandson of Gusri Khan and the chief of the Qosot Mongols in Central Tibet, led to the resignation of the Desi and the complete take-over of political power by Lhazang Khan, who later allied himself with the Manchus and sent the young Dalai Lama into exile.

Lhasang Khan was himself defeated and killed by Dzungar Mongols who had come to Tibet at the invitation of the monks of the three big Gelugpa monasteries in Lhasa. The Dzungars, who were staunch followers of the Gelugpa tradition, were not content with the death of Lhazang Khan. They proceeded to persecute the adherents of the Nyingamapa sect. This brought about a feeling of disenchantment against their presence among sections of the Tibetan people.

When Kalsang Gyatso, the reincarnation of the Sixth Dalai Lama, was discovered in Lithang, in eastern Tibet, there was a struggle among various tribes of the Mongols and the Manchus to gain control over him so that they could exercise their influence in Tibet. The Manchus were successful in this endeavor and so it was that in 1720 the Manchus sent in troops to escort the young Dalai Lama and also avenge the death of their ally, Lhazang Khan. At the same time, Tibetan troops under Khangchennas and Pholhanas took advantage of the situation to attack the Dzungars, who fled with as much loot as they could take with them.

When the Manchu troops entered Lhasa, the Dzungars hact already left. But they had other designs and when their troops finally left in 1723 they left behind a Resident or Amban ostensibly to serve the Dalai Lama but in fact to look after their own interests. This was the beginning of Manchu interference iri Tibetan affairs. The Manchus also put up their own nominee as the Tibetan Regent against Tibetan wishes. A few years later the Manchu nominee was killed and then the Manchu Emperor, Yung Cheng, sent a military force which was the first time the Manchus invaded Tibet. The Manchu force in 1727 tried to bring changes in the administration of Tibetan Government. The Manchu Emperor also tried to buy the allegiance of certain Tibetan princes, chieftains and lamas by giving many of them seals of office. But the Tibetans regarded the seals as a compliment and did not acknowledge them as a mark of vassalage. However, the Manchu Residents (Ambans) began to meddle in Tibetan state matters whenever the opportunity arose.

The Tibetans were repelled by the extent of Manchu intrigues when the Manchu Resident murdered the Tibetan Regent. The Tibetans retaliated by massadring the Manchus in Lhasa. Again the Manchus invaded Tibet in 1749 and they tried in vain to increase the power of the Manchu Resident.

In 1786 the Gurkhas invaded Tibet. The cause for this invasion went back a few years before the Gurkhas had gained full control of Nepal. Nepal had started adding copper to the silver coins which they were supplying to Tibet. In 1751 the Seventh Dalai Lama had written to the three Newari Kings, who ruled over the principalities of Kathmandu, Patan and Bhatgaon, to protest against this practice. When Prithvi Narayan, chief of the Gurkhas, overthrew the Newari rulers he was similarly apprised of the situation.

Another sore point in the relations between the Gurkhas and the Tibetans had been the intervention of Tibet in the Gurkha invasion of Sikkim. Tibet offered help to Sikkim and a treaty was concluded between Nepal and Sikkim in the presence of two

Tibetan representatives. The Gurkhas resented this interference and were looking for an excuse to attack Tibet. Such an opportunity arose in the controversy over the third Panchen Lama’s personal property which was being claimed by the Panchen’s two brothers, Drugpa Tulku and Shamar Tulku. The latter hoped to use the backing of the Gurkhas for his claim. The Gurkhas used the claim of Shamar Tulku and invaded Tibet.

The Eighth Dalai Lama, then 26 years old, requested the Manchu Emperor, Ch’ien Lung, for temporary military assistance. The Manchu army which entered Tibet in 1792 became more harmful to the Tibetans and they again tried to increase the power of the Manchu Resident. Further, Ch’ien Lung sent a golden urn from Peking and declared that future reincarnations of the Dalai Lama and other important lamas should be determined by putting the names of the candidates in it and extracting one at random in the presence of the Manchu Resident. This imperialist imposition was not adhered to by the Tibetans and the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, whose own choice had not even been referred to the Manchus, publicly abolished this form.

During this period Tibet was invaded several times and the Manchu Resident at Lhasa engaged in nefarious intrigues and meddled in Tibetan state affairs. But Tibet never lost her sovereignty. The Tibetan people recognized the Central Tibetan Government, headed by the Dalai Lama, as the only legal Government of Tibet.

The sovereignty of Tibet was further shown in her dealings with Nepal in 1856 when a treaty was signed between the two countries without reference to China. In the internal affairs of Tibet, the sovereignty of the Central Government of Tibet at Lhasa was most clearly illustrated in the internal war which broke out during the middle of the nineteenth century between the chieftain of Nyarong on the one side and the King of Derge and the Horpa princes on the other. The Tibetan Government sent an army, crushed the Nyarong Chief, whose invasion of his neighbour was the cause of the trouble, and set up a Tibetan Governor in his place, charging him with the general supervision of the affairs of Derge and the Horpa principalities.

In 1876, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thupten Gyatso, at the age of 19, took charge of the duties of state from Regent Choekyi Gyaltsen Kundeling. He was an outstanding personality and helped Tibet to reassert her rightful sovereignty in international affairs.

At this period the British had close and profitable ties with China. The Chinese had persuaded the British that they exercise ‘suzerainty’ over Tibet. Therefore on September 13, 1876, the Sino-British Chefoo Convention, which granted Britain the ‘right’ of sending a mission of exploration into Tibet, was signed. The mission was abandoned when the Tibetans refused to allow them on the grounds that they did not recognise China’s authority. Two more similar agreements, the Peking Convention of July 24, 1886 and the Calcutta Convention of March 17, 1890, were also repudiated by the Tibetans.

The Tibetan Government refused to have anything to do with the British who were dealing over their heads with the Chinese. This coincided with new contacts between Russia and Tibet around 1900-1.

There followed an interchange of letters and presents between the Dalai Lama and the Russian Czar. This strengthened British fears about Russian involvement in Tibetan affairs. As the Russian power in Asia was growing, the British Government felt that their interest was at stake. Tibet was invaded by a British expeditionary force under Colonel Younghusband, which entered Lhasa on August 3, 1904.

Younghusband

Younghusband

A treaty was signed between Tibet and Great Britain on September 7, 1904. During the British invasion Tibet conducted her affairs as an independent country. Peking did not so much as protest against the British invasion of Tibet.

When the British invaded Tibet, the 13th Dalai Lama went to Mongolia. The Manchus, who were then ruling China, made one last attempt to interfere in Tibet through the military campaigns of the infamous Chao Erhfeng. Mhen the Dalai Lama was in Kumbum monastery in the province of Amdo, he received two messages – one from Lhasa, urging him to return with all speed as they feared for his safety and could not oppose the intruding troops of Chao Erhfeng, and the other from Peking, requesting him to visit the Chinese capital. The Dalai Lama chose to go to Peking with the hope of prevailing upon the Chinese Emperor to stop the military agression against Tibet and to withdraw his troops.

When the Dalai Lama finally returned to Lhasa in 1909, he found that, contrary to all the promises he had received in Peking, Chao Erhfeng’s troops were at his heels. During the annual Monlam festival of 1910, some 2,000 Manchu and Chinese soldiers under the command of General Chung Ying entered Lhasa and indulged in carnage, rape, murder, plunder, and wanton destruction. Once again the Dalai Lama was forced to leave Lhasa. He appointed a Regent to rule in his absence and left for the southern town of Dromo with the intention to go to British India if necessary. Events in Lhasa and the pursuing Chinese troops forced him to leave his country once again.

In India the Dalai Lama and his ministers appealed to the British Government to help Tibet. Meanwhile the Manchu occupation force tried to subvert the Tibetan Government and to divide Tibet into Chinese provinces – exactly what, not half a century later, the Communist Chinese would do.

But, when the news of the 1911 Revolution in China reached Lhasa, the Chinese troops mutinied against their Manchu officers and attacked the Amban’s residence. Fighting broke out between rival Manchu and Chinese generals. Then, in a desperate attempt to regain their dwindling hold in Lhasa, the Chinese attacked the Tibetans. By then, however, the Tibetans had reorganised themselves with orders coming from the Dalai Lama in India. Chinese troops in Lhasa, and elsewhere in Tibet were overcome by the Tibetans and finally expelled in 1912. During this period of fighting and confusion the new ruler of China, President Yuan Shih-kai, tried to send military reinforcements to the beleagured troops while at the same time trying to placate the Tibetans. He apologised for the excesses and

said that he had restored the Dalai Lama who wrote back saying that he was not asking the Chinese Government for any rank as he intended to ezercise both spiritual and temporal rule in Tibet and declared Tibet’s independence.

…

The Great Thirteeth Dalai Lama …….

The Great Thirteeth Dalai Lama …….

Last of the Chinese troops leaving Tibet for repatriation via India 1913

In January 1913 a bilateral treaty was signed between Tibet and Mongolia at Urga. In that treaty both countries declared themselves free and separate from China.

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama, having returned from India i.n January 1913, issued a formal declaration of the complete independence of Tibet, dated the eighth day of the first month of the Water-Ox year (March 1913). The document also clarified:

“Now the Chinese intention of colonising Tibet under the patron-priest relationship has faded like a rainbow in the sky”.

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama started international relations, introduced modern postal and telegraph services and, despite the turbulent period in which he ruled, introduced measures to modernise Tibet. On December 17, 1933 he passed away.

The following year a Chinese mission arrived in Lhasa to offer condolences, but in fact they tried to settle the Sino-Tibetan border issue. After the chief delegate left, another Chinese delegate remained to continue discussions. The Chinese delegation was permitted to remain in Lhasa on the same footing as the Nepalese and Indian representatives until he was expelled in 1949.

In September 1949, Communist China, without any provocation, invaded Eastern Tibet and captured Chamdo, the headquarters of the Governor of Eastern Tibet. On November 11, 1950, the Tibetan Government protested to the United Nations Organisation against the Chinese aggression. Although El Salvador raised the question, the Steering Committee of the General Assembly moved to postpone the issue.

On November 17, 1950, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama assumed full spiritual and temporal powers as the Head of State because of the grave crisis facing the country, although he was barely sixteen years old. On May 23, 1951 a Tibetan delegation, which had gone to Peking to hold talks on the invasion, was forced to sign the so-called “17-point Agreement on Measures for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet”, with threats of more military action in Tibet and by forging the official seals of Tibet.

The Chinese then used this document to carry out their plans to turn Tibet into a colony of China disregarding the strong resistance by the Tibetan people. What is more, the Chinese violated every article of this unequal ‘treaty’ which they had imposed on the Tibetans.

On September 9, 1951 thousands of Chinese troops marched into Lhasa. The forcible occupation of Tibet was marked by systematic destruction of monasteries, suppression of religion, denial of political freedom, widespread arrests and imprisonment and massacre of innocent men, women and children.

On March 10, 1959 the nation-wide Tibetan resistance culminated in the Tibetan National Uprising against the Chinese in Lhasa. The Chinese retaliated with a ruthlessness unknown to the Tibetans. Thousands of men, women and children were massacred in the streets and many more imprisoned and deported. Monks and nuns were a prime target. Monasteries and temples were shelled.

On March 17, 1959 the Dalai Lama left Lhasa and escaped from the pursuing Chinese to seek political asylum in India. He was followed by unprecedented exodus of Tibetans into exile. Never before in their history had so many Tibetans been forced to leave their homeland under such difficult circumstances. There are now more than one hundred thousand Tibetan refugees all over the world.

It has been almost 40 years since Chinese occupied Tibet and the destruction of a unique

Culture is still going on Tibet, yet the world has not come in aid of Tibet, only lip service.

src = http://www.friends-of-tibet.org.nz/tibet.html